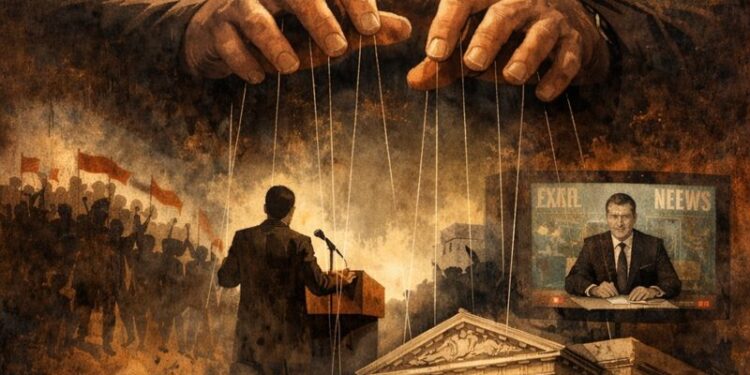

Democracies rarely fail in dramatic moments. They do not always collapse under coups or revolutions. More often, they erode quietly—through rules that bend, institutions that accommodate excess, and authority that slowly replaces accountability.

India’s governance challenge today is not merely corruption or inefficiency. It is something subtler and more dangerous: the steady normalisation of abuse through formal power. When wrongdoing acquires legitimacy, it no longer looks like crime. It looks like procedure.

Across sectors, a disturbing pattern is visible. For almost every excess, there exists an institutional cover. For every abuse, a designation. For every failure, a justification embedded in process.

Policing: Discretion Without Oversight

Policing is the most immediate interface between the state and the citizen. It is also where discretionary power is at its highest—and oversight, often, at its weakest.

Data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) consistently shows a paradox: custodial deaths, illegal detentions, and allegations of excess force remain high, yet convictions of police personnel remain negligible. In many years, conviction rates in custodial death cases have hovered in the low single digits.

The problem is not the absence of laws. Supreme Court directives—from Prakash Singh vs Union of India to guidelines on custodial safeguards—are clear. The problem lies in enforcement. Internal inquiries replace independent investigation. Departmental action substitutes criminal accountability.

As one former police reform committee member once observed, “When discretion becomes culture, legality becomes optional.”

In governance terms, this is institutional absorption of abuse. The police station, instead of being a site of rule enforcement, becomes a zone of negotiated power—where legality is flexible, and accountability conditional.

Judiciary: Authority Without Transparency

The judiciary remains one of India’s most trusted institutions. Yet trust cannot be a substitute for transparency.

Judicial independence is essential, but independence without accountability risks creating what legal scholars call “opaque authority.” Delays running into decades, inconsistent standards for contempt, and the absence of a transparent appointments mechanism have increasingly drawn public scrutiny.

According to government submissions to Parliament, over 50 million cases remain pending across Indian courts. Justice delayed is no longer an exception; it is systemic.

Former Supreme Court judge Justice Madan Lokur once noted that “Delay is not a procedural issue; it is a denial of rights.” Yet institutional incentives to resolve delays remain weak.

The governance concern here is not judicial intent, but judicial insulation. When authority cannot be questioned, even legitimate power begins to appear arbitrary. The courtroom risks becoming not just a forum for justice, but a theatre of dominance—where process outweighs outcome.

Politics: Mandate as Moral Clearance

Electoral democracy is India’s great strength. But elections confer authority, not moral immunity.

Political corruption cases illustrate this dilemma sharply. According to Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) data, over 40% of sitting MPs have declared criminal cases against them, including serious charges. Yet electoral success often reframes allegation as vindication.

In governance practice, this creates a dangerous equivalence: that winning votes equals winning absolution.

Policy failures, regulatory capture, and resource misallocation are no longer judged on merit, but on arithmetic. Numbers replace norms. Mandate replaces morality.

As political scientist Pratap Bhanu Mehta has written, “Democracy without ethics becomes a competition of impunities.”

Media: From Watchdog to Executioner

A free press is central to democratic accountability. But freedom without responsibility risks becoming spectacle.

India’s media ecosystem has expanded rapidly, yet regulation has struggled to keep pace. Trial by media, selective outrage, paid news, and algorithm-driven amplification have blurred the line between reporting and adjudication.

The Editors’ Guild of India and the Press Council have repeatedly flagged ethical decline, but enforcement powers remain limited. Meanwhile, defamation laws and strategic litigation often chill investigative journalism, creating a perverse imbalance: sensationalism thrives, scrutiny suffers.

A senior media scholar once remarked, “We have regulation without teeth, and freedom without conscience.”

In governance terms, the media’s role has shifted—from accountability mechanism to power broker. Reputation becomes collateral damage in the race for narrative dominance.

Faith, Culture, and Social Legitimacy

Even moral institutions are not immune. Religion, cinema, and popular culture increasingly function as legitimacy factories—rebranding exploitation as aspiration, indulgence as enlightenment, and power as destiny.

This is not merely a cultural issue; it is a governance concern. When moral authority is privatised, accountability dissolves. When faith shields excess, law hesitates.

The Core Governance Failure

What links these sectors is not coincidence, but design failure.

India has built strong institutions, but weak feedback loops. Authority travels downward efficiently; accountability rarely travels upward. Designations protect individuals. Procedures absorb misconduct. Time erodes consequences.

This is why scandals fade without closure. Why inquiries replace outcomes. Why outrage exhausts itself without reform.

Democracy, in such conditions, does not break. It corrodes—slowly, silently, legally.

Restoring Friction

Good governance is not about perfection. It is about friction . Independent oversight bodies with real powers. Transparent appointments. Time-bound judicial processes. Police reforms that separate investigation from enforcement. Media regulation that protects free speech while enforcing ethics.

Most importantly, a cultural reset where authority is seen not as entitlement, but as an obligation. As governance expert Yamini Aiyar has argued, “Institutions don’t fail because of bad people alone; they fail because incentives reward the wrong behaviour.”

Until those incentives change, power will continue to masquerade as policy. And that—not corruption headlines or political theatre—is India’s most urgent governance challenge.